Goodbye, Silicon Valley, hello, Atlanta: Black entrepreneurs part of new migration to South

ATLANTA — Over an iPad and a cup of tea, Marcus Blackwell Jr. is talking up his mobile app that uses music to help kids learn math. Sitting across from him at a sleek wood table is Jewel Burks Solomon who, after selling her startup to Amazon, invests time and money in helping other entrepreneurs make their mark in the tech industry.

As Blackwell shows off how algebra formulas in Make Music Count play melodies and chords from popular hip-hop and pop songs, Solomon counsels him on everything from how to get exposure to how to land funding for his app.

This kind of informal coaching session happens hourly in cafes all over San Francisco and Palo Alto, California. The difference here: Nearly everyone in this room is black.

Welcome to the city that’s emerging as the nation’s black tech capital. For a growing number of African-Americans in the tech world, Atlanta is beckoning. Weary of coastal hubs that don’t reflect America’s growing diversity, they are packing up their lives and careers for a city with a rich history of entrepreneurship, a booming black middle class, affordable quality of life and a small but growing tech scene.

Nowhere is Atlanta’s cresting wave of black innovation more evident than here at The Gathering Spot, a members-only, co-working and business networking hub on the site of a turn-of-the-century railway yard west of downtown Atlanta. You never know who you might run into: Voting rights activist Stacey Abrams, who narrowly lost the 2018 race for governor of Georgia, rappers T.I. and Killer Mike, the cast of “Greenleaf” from the Oprah Winfrey Network, and a who’s who of the local digerati, like Solomon.

“I don’t think there is a better place in the country if you’re a black entrepreneur to be,” Ryan Wilson, co-founder of The Gathering Spot, says of Atlanta. “I definitely stand as an example of what’s possible in this city if you really stay rooted here.”

Even as tech companies pour money into increasing the diversity of their work forces, African-Americans remain sharply underrepresented in tech jobs nationwide. But not in the city that’s been dubbed Silicon Valley of the South.

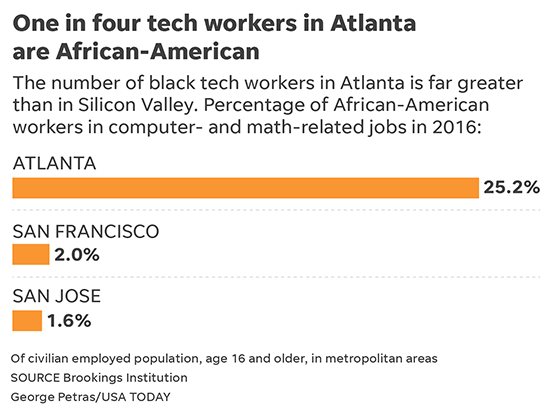

One in four tech workers in the Atlanta metropolitan area are African-American, significantly more than San Jose, California, where 2.5 percent of the tech workforce is black, and San Francisco, where 6.4 percent of the tech workforce is black, according to a Brookings Institution study on black and Hispanic under-representation in the industry.

Opportunity isn’t distributed equally at all levels, however, even here. Though Atlanta’sblack workforce in tech is much larger, so is the equity gap. Black workers’ representation in technical positions in the region is 8 percentage points below their presence in the workforce, the Brookings Institution found.

Like in Silicon Valley, white men dominate the leadership of tech companies in Atlanta. Blacks make up 5 percent of executives and 11 percent of managers at area tech companies, according to regional data from the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. And venture capital dollars aren’t much easier to come by in Atlanta than in Silicon Valley for black entrepreneurs.

For years, investors mostly flew through – not into – the city. Winds have begun to shift southward, sending a sprinkling of venture capital Atlanta’s way. More than $1 billion was raised in 2017 and nearly $1 billion in 2018, four times the amount tech financiers invested in the area a decade ago, according to data from the analytics firm PitchBook.

Still, the volume in Atlanta barely registers on the scale of the massive wealth-generating machine of Silicon Valley, and little of that money is reaching black entrepreneurs.

“There isn’t a lot of early-stage investment flowing into African-American startups,” says Kathryn Finney who runs an organization, Digitalundivided, which prepares black and Latina tech founders for pitch meetings with venture capitalists. “So Digitalundivided teaches Atlanta-based founders to focus on building a solid business and then seek funding for growth.”

Atlanta draws Silicon Valley transplants

None of these downsides have undercut the enthusiasm of recent transplants. In December, when one of the nation’s most prominent black entrepreneurs, Tristan Walker, sold his startup to consumer giant Procter & Gamble, he sent tremors through Silicon Valley with the announcement that he was also relocating Walker & Company Brands to Atlanta.

His modern personal care line for people of color, from shaving products to shampoo, has raised millions from venture capitalists and the likes of rapper Nas and singer-songwriter John Legend, targeting a market worth billions but woefully underserved. Walker, who runs a majority-minority company, says he wanted to bring his business closer to his customers and to the pulse of black culture.

“It’s such a thrilling time for the celebration of blackness and the hope of what that can mean for this country,” he says.

The cross-country move comes six years after Walker co-founded Code2040, a nonprofit that funnels African-American and Hispanic engineers into tech companies.

“I can’t count how many articles have been written on the dearth of diversity in Silicon Valley, yet the problem’s not getting better. And why?” He lets the question hang in the air. “There’s no reason why it shouldn’t or wouldn’t.”

Silicon Valley may have the nation’s greatest density of genius per square mile, he says, but Atlanta lays claim to the greatest density of black genius. “The feeling I get when I go to Atlanta now,” he says, “is the same feeling I got in 2008 when I moved to Silicon Valley.”

Late last year, Jareau Wadé, vice president of growth at a financial tech company, Finix Payment, traded a $3,800-a-month townhouse that he rented but could not afford to buy in the Bay Area for a mortgage on a four-bedroom home in Atlanta that’s less than half that.

It wasn’t just the quality of life and cost of living differences. Wadé says he and his wife longed to raise their 6-month-old daughter closer to family and to the black community.

“Black people can’t just move anywhere in the U.S. and expect to live near other black people,” he says. “So when black families move to the Bay Area the absence of black people is conspicuous.”

That feeling of isolation extended to work. Wadé recalls spotting someone he knew one day in his startup CEO’s office and poking his head in to say hello. “How do you two know each other?” the CEO asked. “We are both black in tech,” Wadé replied.

Silicon Valley wasn’t the right fit for Sheena Allen, either. Allen, who grew up in rural Mississippi and whose startup, CapWay, is a digital alternative to traditional banking, decamped to Atlanta in January to be in the southern capital of financial tech. She first landed in Silicon Valley in 2012 and returned in 2018, only to discover that, despite all the industry talk about becoming more inclusive, she was still the only black person in the room.

“They call Atlanta the capital of black excellence, and I do see a lot of people of color here. It’s also a melting pot of fashion, athletics, entertainment, music, reality TV,” she says. “For me, that makes a huge difference.”

‘We are just warming up’

Paul Judge, a veteran of successful tech companies and widely considered the godfather of the Atlanta tech scene, has been spreading the word for the past two decades.

In 2014, Judge published a guide to Atlanta’s startup scene on the tech news site Pando titled, “Hip-hop, housewives and hot startups.” “Many people outside of Atlanta are more familiar with the former: hip-hop and ‘real’ housewives,” he wrote at the time. “Of those two things, one makes us proud and one makes us, let’s just say, not so proud. Hot startups though – we’ve been busy on that front.”

Today, the latest security firm he co-founded, Pindrop, which raised another $90 million in December, is spread out over three floors of the historic Biltmore Hotel, just a quick jog from TechSquare Labs, where Judge helps the ideas of fellow entrepreneurs take flight. His fiance, Tanya Sam, is director of partnerships at TechSquare Labs and – ironically – recently joined the “Real Housewives of Atlanta” cast.

“It has become very clear that what is occurring in Atlanta is unique,” Judge says. “We have to keep nurturing it and get better telling the world about it.”

That philosophy is behind his recent investment in Atlanta’s A3C Festival and Conference. He’s working to bring big Silicon Valley names to the annual shindig that serves up music, hip hop, culture and tech each October. His vision: an event that rivals Austin’s South by Southwest or the Aspen Ideas Festival.

“This next chapter in Atlanta is going to be exciting,” Judge says. “We are just warming up.”

Melting pot of colleges, corporations and culture

Regions around the country – New York, Boston’s Route 128 and Austin, Texas – have attempted to replicatethe alchemy of the Bay Area, with its deep-pocketed investors, risk-taking culture, world-class universities, crush of technical talent and track record of turning startup dreams into breakout successes.

Atlanta has its own competitive edge with a melting pot of colleges (Georgia Tech and historically black colleges such as Morehouse and Spelman, which are producing more black engineers than anywhere in the country), major corporations (Atlanta is home to one of the largest concentrations of Fortune 500 companies, including Coca-Cola and Home Depot) and chart-topping culture in film, television and music (filmmaker Tyler Perry, musician and actor Donald Glover and rap duo Outkast, not to mention “Black Panther,” which was filmed in and around Atlanta).

Tech is already a significant player here, accounting for 12.5 percent, or $42 billion, of the city’s economy. And its national profile is rising. Atlanta ranks in the top 10 “tech towns” in the nation, outpacing traditional strongholds such as Boston and Washington, D.C., according to CompTIA, a tech industry trade group.

Job postings run into the tens of thousands. The tech labor pool has increased nearly 35 percent over the past five years, the third fastest pace in the nation, and faster than the Bay Area, real estate firm CBRE says.

“The tech industry is just growing rapidly in terms of the entrepreneurship and the startup space,” says Marcellus Haynes, founder of Atlanta’s Technologists of Color Meet-up, which has an email list of 2,600. “We are creating a fertile environment that a lot of companies want to take advantage of.”

What might put Atlanta over the top is the racial diversity of its tech industry and a groundswell of activity to boost opportunities for blacks and other entrepreneurs of color. Solomon flirted with moving to Silicon Valley in 2013 when she founded her company Partpic which made software that lets you point a smartphone camera at a piece of hardware to find a replacement without knowing the name of the supplier or the part. Today, she’s scouting black entrepreneurs all over the country in hopes of luring them to Atlanta, too.

“I think Atlanta has just about everything a startup community needs,” Solomon says. “You just have folks that are willing to help.”

Atlanta’s history as a black mecca

The welcome sign here has been blinking since after the Civil War. The city transformed into a black mecca in the 1970s under the stewardship of Maynard Jackson, Atlanta’s first black mayor and great-grandson of slaves who won the first of three terms in 1973 and oversaw the construction of what would become the nation’s busiest airport.

Today, African-Americans are reversing the great migration, abandoning the Bay Area, Los Angeles, New York, Chicago and Detroit to reclaim cities in the South.

Brookings Institution demographer William Frey, author of “Diversity Explosion: How New Racial Demographics are Remaking America,” says Atlanta leads all other metropolitan areas in black migration, increasing more than five-fold from 1970 to 2017.

Leading that migration are younger, highly educated blacks who want quality of life without the avocado toast price tag. Over 99 percent of Atlanta zip codes – 210 out of 212 – are less expensive than the cheapest zip code in the San Jose metro area, according to Bert Sperling, founder of Best Places, a website that ranks locations across the United States. That means you can trade a $200,000 salary in San Francisco for a $75,747 salary in Atlanta and not sacrifice a thing.

Another big draw for African-Americans is the large number of entrepreneurs. Some 20 percent of the black working population in Atlanta is self-employed, the highest proportion in the nation, according to a study from demographer Joel Kotkin, a presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman Universityin Orange, California, and executive director of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism.

In a majority-black city where 22.4 percent of residents live below the poverty level, black tech entrepreneurs are jumping at the chance to work in a place supportive of tackling issues affecting black people and marginalized communities.

Horace Williams launched Empowrd, an app that provides information on elected officials and connects people with advocacy groups, in 2015 after George Zimmerman was acquitted of killing Trayvon Martin in Florida in hopes of getting more black people to take part in the democratic process.

In 2017, Jasmine Crowe founded Goodr, a mobile app that fights hunger and food waste by getting restaurants and companies to donate surplus food to homeless shelters, affordable housing communities and other agencies.

Blackwell says his app, which is being tested in Atlanta Public Schools, was inspired by his desire to see black children excel in math. “I think what’s missing with education is meeting students where they are and the communities they come from,” Blackwell says. “It’s important for me to help close this achievement gap.”

Morgan DeBaun, chief executive of Blavity, a popular digital media hub for black millennials, says she decided to open a tech office in Atlanta last year to take advantage of all this local black engineering talent.

DeBaun spends a week in Atlanta each month. One of her co-founders, Jeff Nelson, the company’s chief technology officer, is based here. She has faith that Atlanta will become a major player in the tech industry.

“The more we are all committed to it, the more it will manifest itself,” she says. “It’s like a self-fulfilling prophecy.”